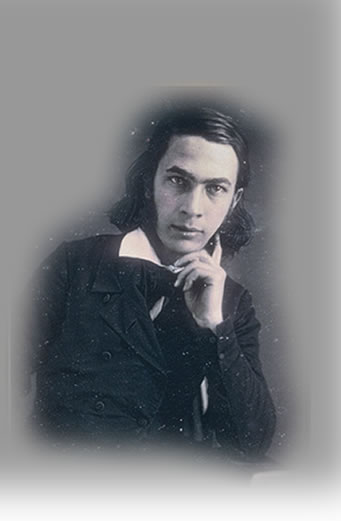

[E] Boz

When Charles Dickens visited Philadelphia

in February 1842, Lippard was an attentive and ambivalent observer.

Over the course of a series of articles on Dickens’ visit, Lippard

articulated in embryonic form a critique of the literary public sphere

(to use the Habermasian term) or the literary field (to invoke Bourdieu’s

category). He described an American literary world invidiously

organized into high and low sectors, controlled by middlebrow idiots,

corrupted by dishonest insider backscratching (the “tickle-me-and-I’ll-tickle-

Several of the articles reprinted

here have been previously attributed to Lippard (E1-2, E11; the latter

is also included under the “City Police” series as A11). But

the others are newly attributed, on the grounds of their remarkable

resemblance to those previously attributed, as well as the thematic

continuity and tonal consistency of all of them. Together

they make up a coherent account of this episode in American literary

history. Throughout these articles, Lippard admired Dickens and

welcomed the prospect of his visit to Philadelphia; but he deplored

the “insipid adulation” (E2) bestowed upon Dickens, scornfully characterized

as the “sycophancy of ’a free and enlightened people’” (E11),

and resented deeply the attempt by a self-appointed clique of “small

potatoes literati” (passim) to monopolize Dickens and cozy up to his

celebrity, while excluding socially-unconnected neophytes like Lippard

who, moreover, worked for penny papers of radical democratic orientation.

He credited Dickens, however, with the ability to see through the fakery

and stupidity of his abject American lionizers.

Of particular interest here is the series of three reports, published on three days in a row, detailing (and mocking) a fancy ball held in New York City to celebrate Dickens’ visit there (E3-5). All of Lippard’s ambivalence about the Dickens phenomenon can be detected here. In the first (E3), there was an incipient tone of mockery (“If Boz had been a very God, he could not have received more adulation and worship”), but all the details of the extravagant event were nevertheless recorded with evident relish. The next day, curiously, the same event was re-told, but with a conspicuously heavier dose of satire, seemingly reflecting sardonically upon the previous day’s admiring attention to the rich details of conspicuous social display. Now Lippard bluntly called this event the “tom-foolery of silly-minded Americans” (E4). One day later again, he ratcheted up the scorn another level: the New York ball was “a complete burlesque of the American character . . . because of the egregious buffoonery of our literary monkeys” (E5). It is as if we can see Lippard’s critique of the false and invidious structure of his literary environment taking increasingly severe shape day by day.